Quantum Patchwork

The Brief

General Relativity (GR) and Quantum Mechanics (QM) are two fundamental yet incompatible areas of Physics, where both seem to be correct but neither of them agree with the other. *

GR was published by Einstein in 1915, and was a theory of how gravity was simply a geometric property of the universal continuum of time and space (spacetime).

The theory worked great on scales the size of the solar system, yet failed at explaining gravity on much greater and much smaller scales.

QM is a huge pillar of modern physics, which is an area that sets out to explain how things work on smaller scales (we're talking 10e-15m in length and smaller). QM is infinitely strange as it appears to suggest that small elementary particles can exist in all possible states (including places) until measured.

*

An example of this disagreement is the information paradox, where GR tells us that anything that falls into an area of extremely warped spacetime is lost forever.

QM, on the other hand, says that information can never be truly lost - albeit extremely tangled.

Stephen Hawking recently claimed to have solved this by showing that matter falling into a black hole can be translated into two-dimensional holograms that sit on the event horizon.

The real challenge, then, is to explain gravity in terms of quantum mechanics and particle physics.

A successful theory of quantum gravitation should explain what happens at the singularity of a black hole - where existing laws of physics make no sense - and why did the Big Bang happen at all.

Quantum Patchwork answers these questions fully by taking general relativity's spacetime and explaining how it works on a microscopic scale.

Stosons

What if spacetime was a universal FIELD of virtual particles of time and space?

And what if we could visualise the entire universe as being composed of an infinite number of 'sheets' of tightly packed particles (like an infinite tiramisu)?

For the sake of efficiency, I'll call these particles 'Stosons' and I imagine them to be layered throughout the entire universe in sheets, or 'stoson membranes'.

Imagine this sheet of spacetime, but on a smaller scale it's made up of tiny particles, and with many other sheets 'stacked' uniformly up to infinity.

Quark Confinement and Photon Emission

The people who think that mass is gained through the consumption of food, you're not wrong.

But this guy called Peter Higgs suggested in the 1960's that small particles called 'Quarks' got their mass from a mechanism called the Higgs field. The more a particle interacts with the Higgs field, the more mass it gains.

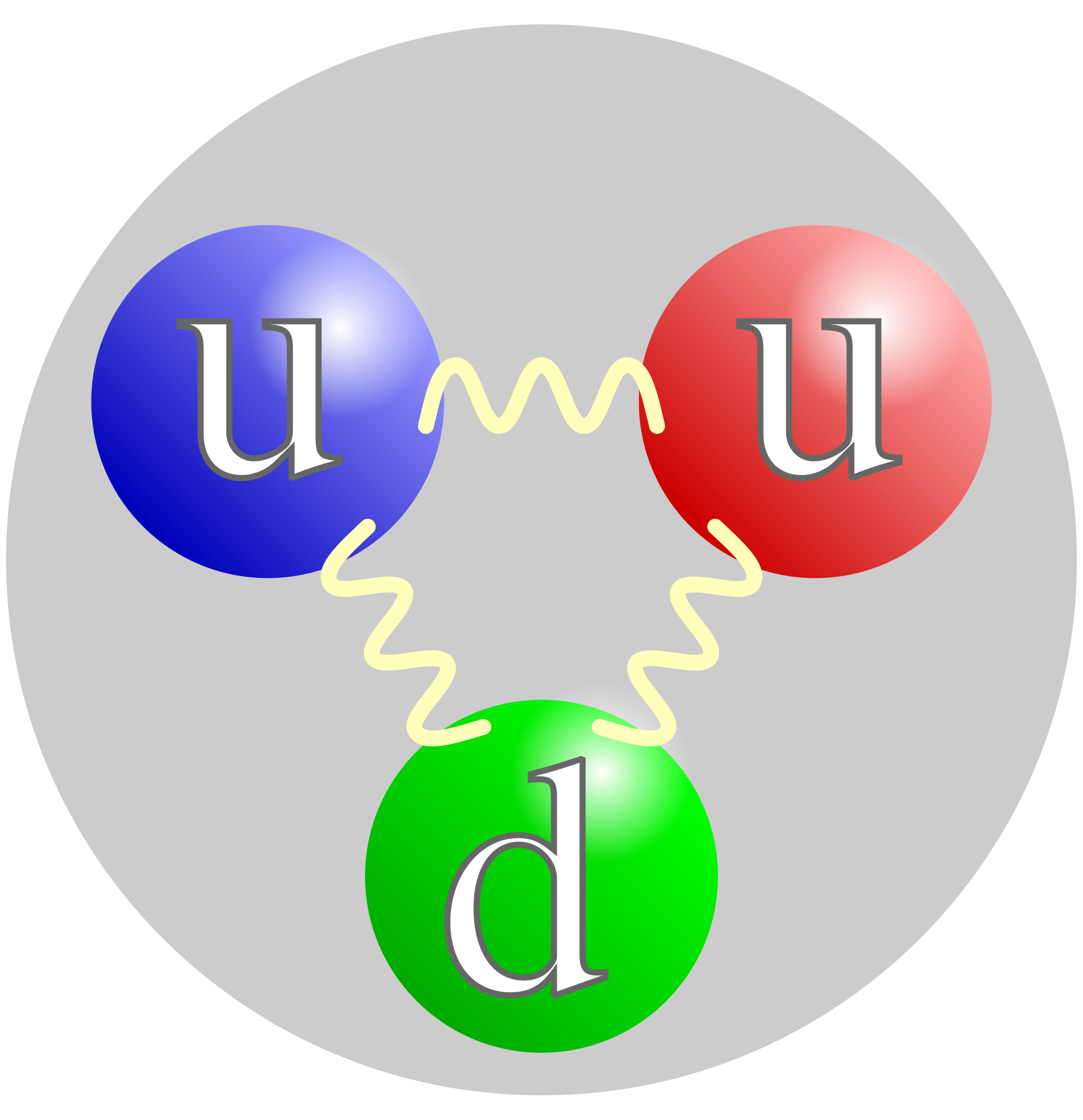

Quarks are sub-subatomic particles that make up bigger particles like Protons and Neutrons.

This is a proton, made of three quarks. Two 'up' quarks and one 'down' quark.

The up quark has a charge of +2/3 and the down quark has a charge of -1/3.

2/3 + 2/3 - 1/3 = 1, which is why the proton has an electrical charge of +1.

The Higgs mechanism explains how quarks get their mass, but can't explain where bigger particles get the rest of their mass.

The proton seems to be many times more heavy than the sum of the three quarks that make up the particle, so it has been suggested that the confinement of these quarks (the compact nature of them) means that the quarks become more energized.

As E=mc^2 (energy is the same as mass), then the proton becomes more heavy.

So particles can become energized and therefore more heavy due to confinement.

Photon emission is when an atom is energized (let's say heated) it gives off this energy as a particle of light - also known as a photon. This is sort of how a laser works.

The photon is a gauge boson of electromagnetism. A boson is a type of particle that carries a force. Electromagnetism is carried by a photon, and the other forces are also carried by other types of boson.

It is said that gravity is carried by a Graviton, yet these haven't been detected yet.

So, energized particles can give off the energisation as a particle.

---------------------------------------------

Imagine if you were to add a huge amount of mass, like a star, to the stoson membranes mentioned earlier.

The stoson particles near the star would suddenly become more densely packed than usual. And with this density, would come energisation of the stoson particles.

I believe that this excess energy would be given off as a Graviton.

The density of the object would lead to more energization of stoson, and therefore more Gravitons to be emitted and consequently a greater force.

But wouldn't the stosons be destroyed once they've been compressed to the limit. No.

Not if the universe is dynamic, then new stosons would be compressed as old ones move away.

So, this model would only work if space is dynamic; guess what the universe is doing. It's expanding.

Now, going back to the idea of E=mc^2 (where E is energy in Joules, m is mass in KG and C is the constant of light - 299,792,458). Because we're talking about particles here, it is possible that these membranes of stosons could just be sheets of spacetime energy.

This sounds a lot like the string membranes in string theory, which are universal 'sheets' of energised elementary vibrating strings.

But what are the implications of there being an infinite number of stoson membranes?

Well, it would indicate that open warps in spacetime couldn't possibly exist. This is because the infinite membranes above the warp would fill the warp in - sort of like how a glass bowl in an infinite sea of water would quickly fill up with the aqueous solution, as air simply doesn't exist.

What we're left with would be different values of spacetime, where the presence of matter marks a place where spacetime stoson membranes are more densely packed.

This idea of different values at different points in space suggests to us that the universe is made up of a field.

Gravitational Waves in terms of Quantum Patchwork

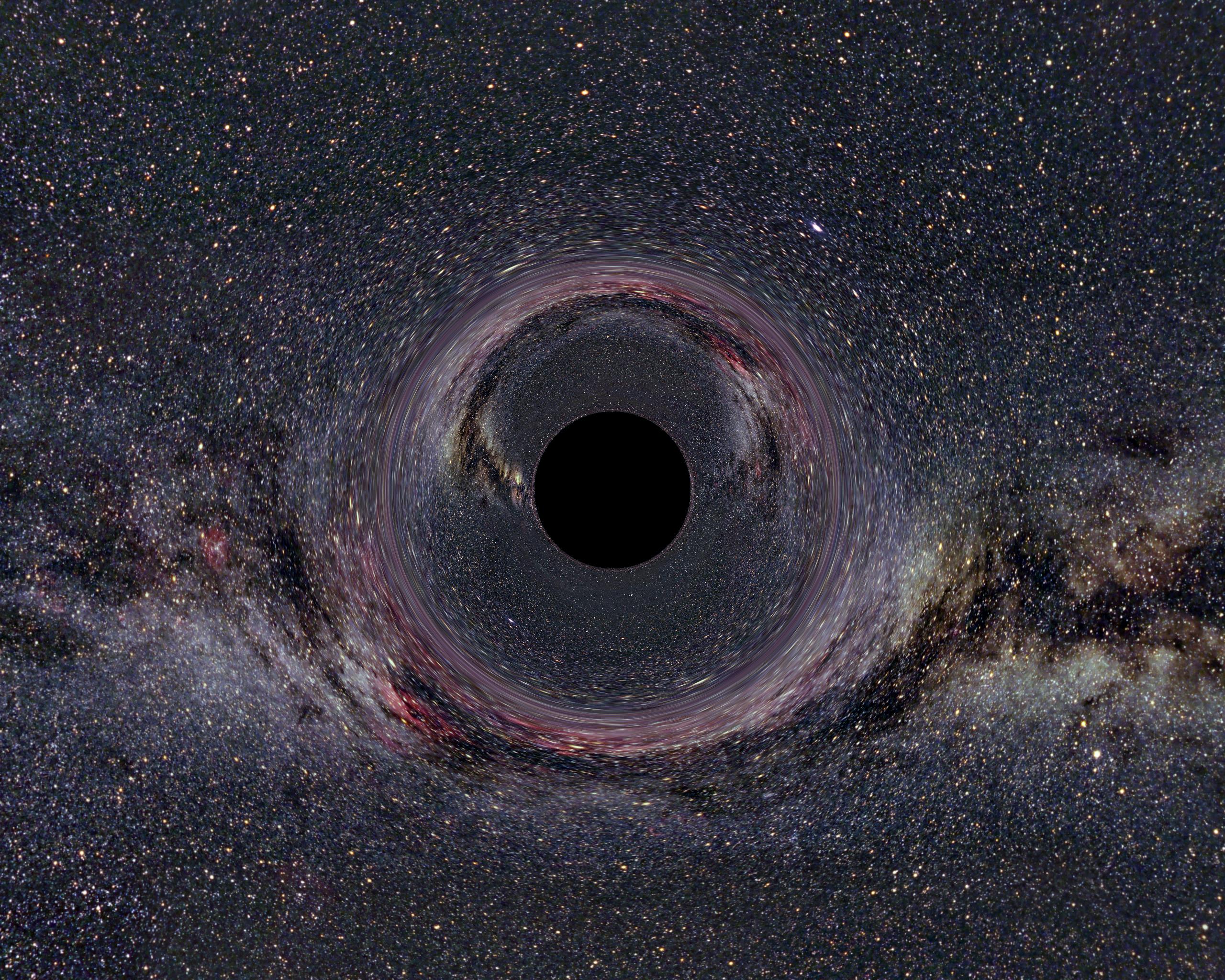

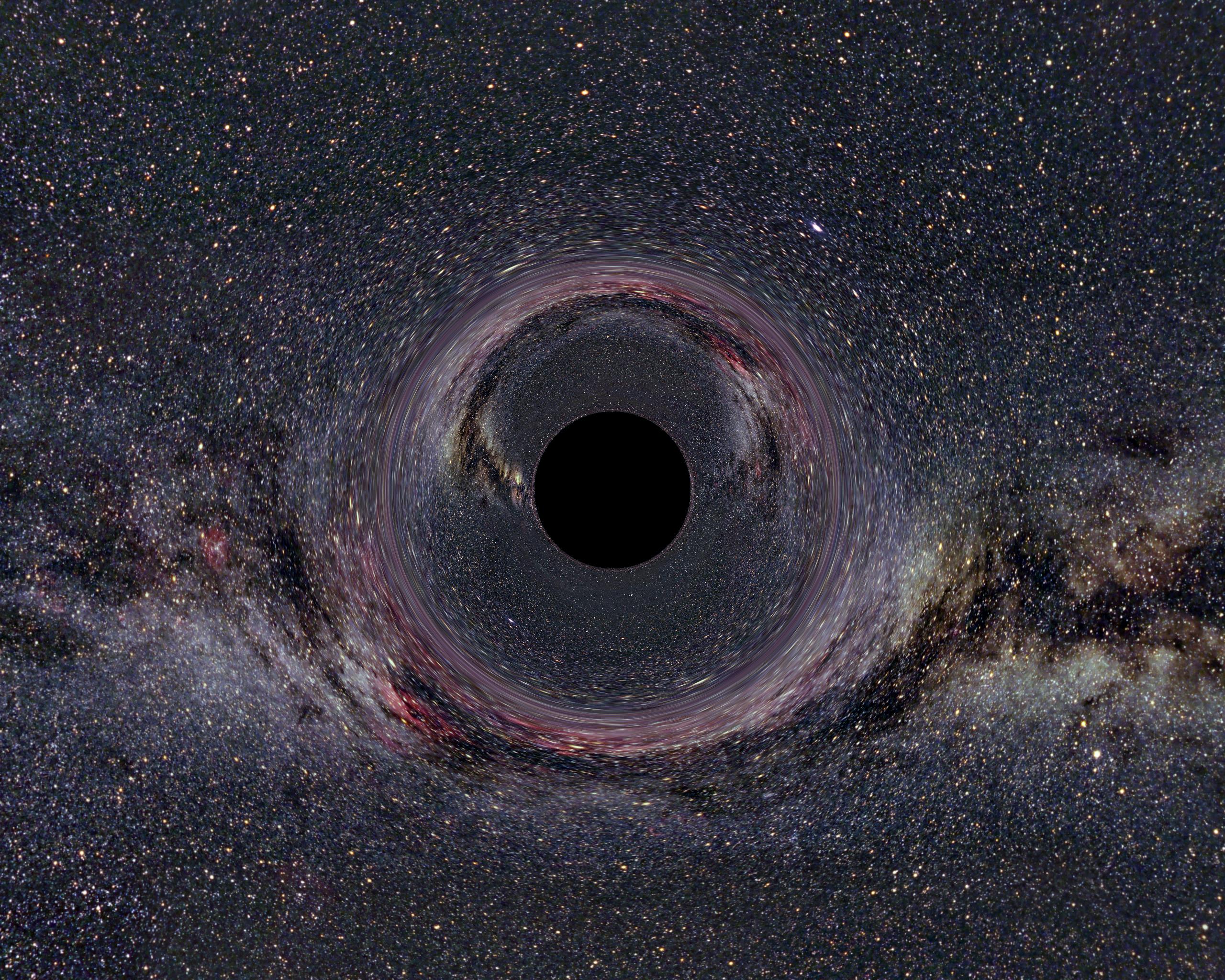

Gravitational waves were predicted by Einstein in his general theory of Relativity. Put simply, when two black holes - for example - collide with one another, the resulting energy is so great that ripples are created in the fabric (not really a fabric by the way) of spacetime.

Imagine throwing a pebble into a lake, the result would be waves moving from the center of collision and outwards. The same thing theoretically applies in space.

When two rotating black holes come close together, the energy of the collision itself is amplified by the rotation - which causes spacetime to swirl as shown below.

This effect was first predicted by Einstein in 1916.

Also around a black hole, is what's called an Ergosphere which is basically a ring of distortion around a black hole's event horizon. This happens because spacetime around the rotating 'Kerr' black hole is actually dragged in around it!

So, how can these gravitational waves be explained on a quantum level?

I have two ideas concerning this, and am still trying to decide upon the most plausible.

The ideas are called 'Graviton Exchange' and 'Membrane Fluctuations'.

Graviton Exchange

This hypothesis came from the idea that when electrons come into contact with one another, they exchange a virtual photon. This is because the photon is the boson of electromagnetism, so when the electrons come close together they exchange a photon and therefore interact with the electromagnetic force which causes them to repel one another.

Now, quarks participate in the strong nuclear force - the force responsible for holding quarks together - and the boson which mediates this is humorously named the Gluon. Quarks exchange gluons inside the subatomic particle.

In the weak nuclear force, a neutrino emits a W+ boson and gives it to a down quark, which in turn gains a slightly more positive charge and becomes an up quark.

What we learn from this is that bosons are exchanged between particles. Anyone could have figured that out.

So what exchanges gravitons? Perhaps it's the stosons.

The infinite number of stosons could constantly be exchanging virtual gravitons between one another, so what you've got are gravitons being emitted and absorbed left right and center - like nits in a classroom of small children.

Now if spacetime is dynamic, adding some kind of mass to it would surely cause gravitons to be thrown off course.

When two black holes come together, so much pressure is being put onto the stoson membranes that gravitons are thrown violently in all directions.

This would however suggest that acceleration is needed for gravitons to be emitted.

[Membrane Fluctuations]

[In progress]

Black Hole Singularities

It is thought that the gravity of a black hole becomes infinite when you get to the black hole's singularity - the singularity is essentially the centre of the black hole where all of the mass is located - and this is because the singularity itself is infinitely dense due to the imbalance of gravity and the force once exerted by the star that the black hole once was,

General Relativity shows us that because gravity is infinitely dense, then the warp in spacetime should be infinitely deep and narrow. There is a problem here, because it doesn't really explain what actually happens at the singularity itself, which is why theories of quantum gravitation are needed.

So how does Quantum Patchwork explain this? Well, we need to go back to the idea that spacetime could be an infinite dynamic field of energy membranes, where the abundance of them means that warps are always filled in by the infinite number of membranes above it.

Energy conservation law says that energy cannot be truly destroyed. If we merge this with the idea that space is moving and that energy can be transferred through confinement, perhaps it's logical to assume that the gravitons of a black hole are given off as some kind of quantised excitation of spacetime itself. As they move away from the black hole, they take away some of the black hole's energy with them. This would eventually decrease the mass of a black hole over time, causing it to evaporate - albeit very slowly indeed. If this is true, then the rate of black hole evaporation should be proportional to the density of the singularity, making the physical size completely irrelevant.

The denser the black hole, the more excitations of spacetime - which would result in the gravitons to leave with more energy, which is also a form of mass.

This idea linked with the idea of Hawking Radiation (where virtual particles can become separated on a black hole's event horizon and the negative mass one decreases the black hole's mass and the positive mass one is able to escape into space forcing it into becoming a real particle) suggests that black holes should evaporate actually faster than we previously expected.

This explains the effects of patchwork's ideas on singularities, but doesn't get to the root of the problem.

How do they actually work?

To explain this we need to go back to the idea of a Tiramisu structure to the universe - where it is composed of different sheets of either energy of time and space, or undetectable particles of time and space.

I will talk about them as being energy for the moment as it seems to be the most realistic.

This sounds a lot like the string membranes in string theory, which are universal 'sheets' of energised elementary vibrating strings.

But what are the implications of there being an infinite number of stoson membranes?

Well, it would indicate that open warps in spacetime couldn't possibly exist. This is because the infinite membranes above the warp would fill the warp in - sort of like how a glass bowl in an infinite sea of water would quickly fill up with the aqueous solution, as air simply doesn't exist.

What we're left with would be different values of spacetime, where the presence of matter marks a place where spacetime stoson membranes are more densely packed.

This idea of different values at different points in space suggests to us that the universe is made up of a field.

Gravitational Waves in terms of Quantum Patchwork

Gravitational waves were predicted by Einstein in his general theory of Relativity. Put simply, when two black holes - for example - collide with one another, the resulting energy is so great that ripples are created in the fabric (not really a fabric by the way) of spacetime.

Imagine throwing a pebble into a lake, the result would be waves moving from the center of collision and outwards. The same thing theoretically applies in space.

When two rotating black holes come close together, the energy of the collision itself is amplified by the rotation - which causes spacetime to swirl as shown below.

This effect was first predicted by Einstein in 1916.

Also around a black hole, is what's called an Ergosphere which is basically a ring of distortion around a black hole's event horizon. This happens because spacetime around the rotating 'Kerr' black hole is actually dragged in around it!

So, how can these gravitational waves be explained on a quantum level?

I have two ideas concerning this, and am still trying to decide upon the most plausible.

The ideas are called 'Graviton Exchange' and 'Membrane Fluctuations'.

Graviton Exchange

This hypothesis came from the idea that when electrons come into contact with one another, they exchange a virtual photon. This is because the photon is the boson of electromagnetism, so when the electrons come close together they exchange a photon and therefore interact with the electromagnetic force which causes them to repel one another.

Now, quarks participate in the strong nuclear force - the force responsible for holding quarks together - and the boson which mediates this is humorously named the Gluon. Quarks exchange gluons inside the subatomic particle.

In the weak nuclear force, a neutrino emits a W+ boson and gives it to a down quark, which in turn gains a slightly more positive charge and becomes an up quark.

What we learn from this is that bosons are exchanged between particles. Anyone could have figured that out.

So what exchanges gravitons? Perhaps it's the stosons.

The infinite number of stosons could constantly be exchanging virtual gravitons between one another, so what you've got are gravitons being emitted and absorbed left right and center - like nits in a classroom of small children.

Now if spacetime is dynamic, adding some kind of mass to it would surely cause gravitons to be thrown off course.

When two black holes come together, so much pressure is being put onto the stoson membranes that gravitons are thrown violently in all directions.

This would however suggest that acceleration is needed for gravitons to be emitted.

[Membrane Fluctuations]

[In progress]

Black Hole Singularities

It is thought that the gravity of a black hole becomes infinite when you get to the black hole's singularity - the singularity is essentially the centre of the black hole where all of the mass is located - and this is because the singularity itself is infinitely dense due to the imbalance of gravity and the force once exerted by the star that the black hole once was,

General Relativity shows us that because gravity is infinitely dense, then the warp in spacetime should be infinitely deep and narrow. There is a problem here, because it doesn't really explain what actually happens at the singularity itself, which is why theories of quantum gravitation are needed.

So how does Quantum Patchwork explain this? Well, we need to go back to the idea that spacetime could be an infinite dynamic field of energy membranes, where the abundance of them means that warps are always filled in by the infinite number of membranes above it.

Energy conservation law says that energy cannot be truly destroyed. If we merge this with the idea that space is moving and that energy can be transferred through confinement, perhaps it's logical to assume that the gravitons of a black hole are given off as some kind of quantised excitation of spacetime itself. As they move away from the black hole, they take away some of the black hole's energy with them. This would eventually decrease the mass of a black hole over time, causing it to evaporate - albeit very slowly indeed. If this is true, then the rate of black hole evaporation should be proportional to the density of the singularity, making the physical size completely irrelevant.

The denser the black hole, the more excitations of spacetime - which would result in the gravitons to leave with more energy, which is also a form of mass.

This idea linked with the idea of Hawking Radiation (where virtual particles can become separated on a black hole's event horizon and the negative mass one decreases the black hole's mass and the positive mass one is able to escape into space forcing it into becoming a real particle) suggests that black holes should evaporate actually faster than we previously expected.

This explains the effects of patchwork's ideas on singularities, but doesn't get to the root of the problem.

How do they actually work?

To explain this we need to go back to the idea of a Tiramisu structure to the universe - where it is composed of different sheets of either energy of time and space, or undetectable particles of time and space.

I will talk about them as being energy for the moment as it seems to be the most realistic.

Here's a simple diagram that I quickly threw together on Microsoft Paint. The darker regions are points of higher density and therefore greater gravitational influence.

[Note: Currently in development, will be elaborated upon daily]